Railways and Retail: the Depāto as an Enduring Urban Chronicle

with Professor Yoko Kawai

with Professor Yoko Kawai

*excerpted from written work done for ARCH3265a: Destruction, Continuation, and Creation

- Architecture and Urbanism of Modern Japan, Fall 2018

"Our city is never fixed; it is always in a state of transition. City is process - no concept is more certain than that"

-Arata Isozaki, Arata in Japanese Space;

excerpted from Kira, Moriko, and Mariko Terada’s Japan towards Totalscape: Contemporary Japanese Architecture, Urban Planning and Landscape

Few would disagree with the above observation of the Japanese city by Arata Isozaki. The quintessential Japanese city’s voracious appetite for the new is balanced with reverence for the old. Of the many spatial endeavors that have formerly or currently contribute to the Japanese city in process, the Japanese department store is an exceptional model that embodies both stability and transition. There is little else of in modern history that can compete with the endurance, inventiveness, and proliferation of the Japanese depāto.

The depāto, or department store, is a cornerstone of Japanese urbanity - a typology that withstands wars and disasters through the sheer force of will of their truly resilient parent corporations. Each time resurrecting established infrastructure to house new, contemporaneous needs. The depāto’s close integration into public transit, social hierarchy, urban fabric, and communal needs have - until now - cemented its place as a precondition to urban life.

“The final section of 'Process Planning' sets forth the way in which architecture that has grown in reverse from the terminal minute is frozen in an instant. In other words, the building ceases to progress towards growth and instead begins moving in the direction of ruin. For this reason, my doctrine ... is closer to the Buddhist doctrine of the impermanence of all things”

The department store as we know it has fully undergone the first sections of what Isozaki characterizes in his Theory of Process Planning - of genesis and development. It is through chronicling the past and present of this singular infrastructural phenomenon that insight can be gained about the factors metabolized into its inception and growth. We will also consider an instance of the typology removed from its native context, briefly surfacing in America, as a foil for determining the efficacy of the model detached from said factors.

Finally, some thought must be given to the future outcomes of physical and architectural space left behind as the typology expires. The depāto is only now passing the point of stasis into ruin, making it a valuable subject for investigation. What determines the pace at which this urban infrastructure is abandoned? Which built inflexibilities are keeping the depāto from another successful reincarnation? And ultimately, what else might come in its place?

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Fundamentally speaking, the key difference between the two models was of scope. The preceding model selectively pursued customers beyond the store, only then investing time and spatial infrastructure in cultivating them as loyal consumers. This pinpointed interaction with urban dwellers had a correspondingly low amount of impact on the surrounding physical environment, contributing to the typology’s extinction. The newer depāto model integrated itself with the most democratizing level of urban street infrastructure, miming visual and procedural cues to the convenience of a larger, if less devoted demographic. Full dependency on the urban conditions made the depāto more open and flexible, ultimately affording a longer urban half-life.

The evolution from cultivation towards convenience is important urbanistically as they fundamentally differ in degrees of self-sufficiency - one generates a placeless appeal where the other must divert from a pre-existing density. In the previous example of Matsuzakaya’s evolution, its original siting followed the established conventions of a hyakkaten: occupying a corner site that had access to two main roads, the dominant transit infrastructure for goods and its roving salespeople. While it did enjoy proximity to Ueno park and was only several blocks away from the Yamanote Line, there was no immediate consideration post-earthquake to connect to these infrastructures in a direct fashion.

The conjoined development of Japanese department stores came from contributors entirely outside the realm of mortar-and-brick retail. Influenced by the success of Mitsukoshi Ginza branch, Hankyu Railways attempted to replicate the success of accessible department stores at commuter junctions, becoming the first railroad conglomerate to generate their own rail-to-retail venture. The railroad company’s first endeavor took place in Osaka, a city largely unaffected by the 1923 earthquake,“investing in shopping and leisure facilities at the central stations where commuters came together” As the first Hankyu department store opened at its Umeda station, this transit oriented strategy spread to a recovering Tokyo. In 1930, just after finishing the rebuilding of their flagship store, Matsuzakaya announced plans to directly connect their existing basement to the Ueno Hirokoji station on the Ginza subway line.

Today it seems impossible to conceive of a version of Japanese retail that doesn’t blend seamlessly into public transportation. Train stations, commuter and city subways alike, teem with the activity of countless vendors. “A walking tour guidebook for lovers published in 1932 suggested that as one of its five ‘date courses’, a young couple could visit ‘The Five Great Department Stores by Subway’, extolling that “the great thing about this tour was that, even if it was raining, the young couple could do all this without even having to put up an umbrella.”

It is possible here to note yet another evolutionary crossroads during the 1930’s - 1940’s, between depāto that had undergone the transformation from single vendor to hyakkaten and beyond and later railroad-affiliated depāto. As the former stores were being rebuilt post-earthquake in concert with new subway lines underground, many stores took after Matszakaya’s approach to ally themselves with the metropolitan subway. Railroad-affiliated depāto like Hankyu, Seibu in 1940, and later Tobu in 1962 continued their dogged pursuit of the sub-urban, sub-cosmopolitan commuter. Through their commitment to the larger interconnected environment, each of the five department store/hyakkaten-depāto strengthens their overall appeal to the average city dweller; a benefit that a suburban Seibu or Tobu store does not compound as more branches are built at distance from each other.

![]()

![]()

The basic operating diagram of a depāto across all franchises follows the same sectional construct: members of the public enter and leave from the basement or ground levels, travel upwards through private sale floors towards public functions of their choosing, ideally making purchases before their departure. Varying public programs - informal food halls, exhibition halls, even community colleges - found their place high on the sectional diagram. Use of western building methods yielded an additional benefit - flattened roofs capable of supporting sizeable program. True to form, the urban depāto placed public amenities on every viable rooftop without fail. In all but the most developed parts of Ginza, these rooftops enjoyed unmatched civic stature as the primary observation decks of their time - in the vein of Tange’s Metropolitan Government Building or today’s Oshiage Skytree.

Even as early as the 1920s, the urban depāto rooftops had begun to engage in a veritable arms race, one that continues to this day - spawning everything from theme parks to petting zoos, mini-golf courses to German beer halls. Each programming trend proffers keen insight into the urban conditions of the day. There is no doubt that much can be gleaned of the collective psyche from the popularity of amusement “skyparks” after WWII, or the recent demand for rooftop cocktail bars.

Whether or not a rooftop has been masterfully filled with program, the occupiable rooftop is a highly desirable component of the prototypical depāto - so much so that department stores without them will feign one with the use of artificial grass, as seen on Tobu in Ikebukuro. The flaws in these skilled facsimiles of free, public space are only noticed when an individual attempts to cross from one roof to the next. Even when all owned by the same conglomeration, pedestrian bridges are carefully drawn from retail floor to retail floor, eliminating the possibility of circumvention by a shrewd individual.

The primacy of rooftop space can be easily understood simply from the working diagram of the depāto. Its greatest value, apart from being a luxury not afforded to small commercial competitors, is as the satisfactory foil to the decidedly public subway basements of these shopping complexes. It completely obfuscates the meaning of a depāto name when one could be referring to either the transit node, the shop floors sandwiched in-between, or a public gathering space - effectively normalizing the private, cementing the enterprise into the experience of the city.

It is again worthwhile to note the marked difference in rooftop primacy in urban versus suburban environments. Although urban depāto rooftops had lost much of their coveted views to the post-war building boom, many suburban depāto are still the standard for building height where they stand. Yet railway depāto have not seen the same investment into creating outdoor sanctuaries atop their social programming. In general, Tobu and Seibu depāto rooftops only satisfy base utilitarian needs, catered to families with young children. Unlike the hyperaware urban depāto, suburban depāto rooftops presuppose an unchanging demographic: yet another point of flexibility the department store infrastructure supports.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

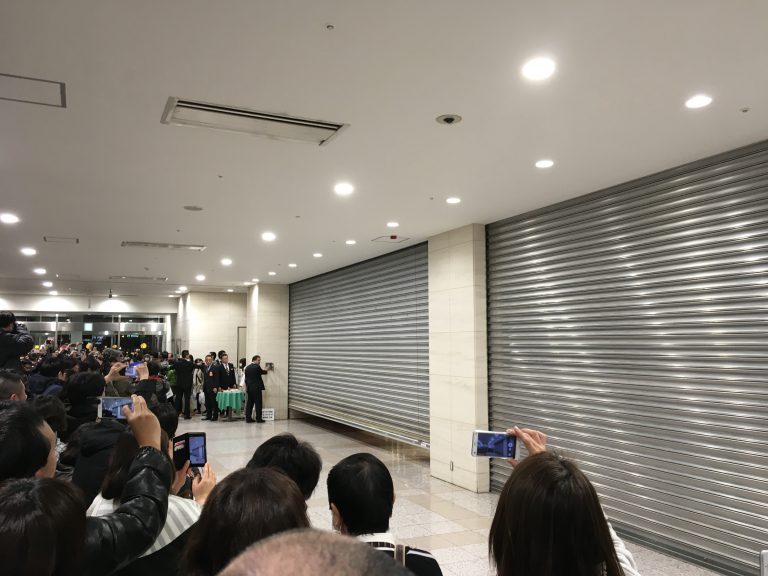

Conclusion: Demise of the Depāto, 1980s to Today

Retrospectively, to chronicle the urban legacy of the Japanese depāto is to understand the exceptional circumstances that allowed it to exist. The existence of such a typology owes as much to Western architectural methods and department store precedent as it did Japan’s Hyakkaten mode of involved consumption and closed country policy.

The depāto cannot exist in a vacuum. Nor can it function as an anchor or draw based on its own merits, as observed in Seibu Los Angeles. It is merely ephemeral infrastructure space between two public arenas operating in perpetuity.

Many of the same observations on the depāto model without mass transit infrastructure in the 1960s can be applied to the depreciating suburban depāto of today. As shopping habits change, it has become more and more difficult for any physical retail store to attract footfall. Although the department store industry has seen declines in the lower two digits since the asset crisis hit, the rail line depāto has been the most affected by market insolvencies. Railway conglomerates have closed more than half of all suburban depāto in the last 15 years, which given the scale of their regional urbanity, is not particularly unexpected.

It is a testament to the efficacy of the urban depāto formula that with critical urban density and the endless capacity to adapt programmatically, new functions have been implemented that have brought sustaining growth. Ikebukuro’s Tobu and Seibu branches are great exemplars of surviving metabolism. Following current trajectories, the former will house only food services and restaurants while the latter continues expanding its current 400+ class dossier into Japan’s greatest community college.

As we near the 100th anniversary of the first transit depāto, we are also approaching a day where there is nothing left of the old department store. It’ll be anyone’s guess what comes next.

![]()

The depāto, or department store, is a cornerstone of Japanese urbanity - a typology that withstands wars and disasters through the sheer force of will of their truly resilient parent corporations. Each time resurrecting established infrastructure to house new, contemporaneous needs. The depāto’s close integration into public transit, social hierarchy, urban fabric, and communal needs have - until now - cemented its place as a precondition to urban life.

“The final section of 'Process Planning' sets forth the way in which architecture that has grown in reverse from the terminal minute is frozen in an instant. In other words, the building ceases to progress towards growth and instead begins moving in the direction of ruin. For this reason, my doctrine ... is closer to the Buddhist doctrine of the impermanence of all things”

The department store as we know it has fully undergone the first sections of what Isozaki characterizes in his Theory of Process Planning - of genesis and development. It is through chronicling the past and present of this singular infrastructural phenomenon that insight can be gained about the factors metabolized into its inception and growth. We will also consider an instance of the typology removed from its native context, briefly surfacing in America, as a foil for determining the efficacy of the model detached from said factors.

Finally, some thought must be given to the future outcomes of physical and architectural space left behind as the typology expires. The depāto is only now passing the point of stasis into ruin, making it a valuable subject for investigation. What determines the pace at which this urban infrastructure is abandoned? Which built inflexibilities are keeping the depāto from another successful reincarnation? And ultimately, what else might come in its place?

Fundamentally speaking, the key difference between the two models was of scope. The preceding model selectively pursued customers beyond the store, only then investing time and spatial infrastructure in cultivating them as loyal consumers. This pinpointed interaction with urban dwellers had a correspondingly low amount of impact on the surrounding physical environment, contributing to the typology’s extinction. The newer depāto model integrated itself with the most democratizing level of urban street infrastructure, miming visual and procedural cues to the convenience of a larger, if less devoted demographic. Full dependency on the urban conditions made the depāto more open and flexible, ultimately affording a longer urban half-life.

The evolution from cultivation towards convenience is important urbanistically as they fundamentally differ in degrees of self-sufficiency - one generates a placeless appeal where the other must divert from a pre-existing density. In the previous example of Matsuzakaya’s evolution, its original siting followed the established conventions of a hyakkaten: occupying a corner site that had access to two main roads, the dominant transit infrastructure for goods and its roving salespeople. While it did enjoy proximity to Ueno park and was only several blocks away from the Yamanote Line, there was no immediate consideration post-earthquake to connect to these infrastructures in a direct fashion.

The conjoined development of Japanese department stores came from contributors entirely outside the realm of mortar-and-brick retail. Influenced by the success of Mitsukoshi Ginza branch, Hankyu Railways attempted to replicate the success of accessible department stores at commuter junctions, becoming the first railroad conglomerate to generate their own rail-to-retail venture. The railroad company’s first endeavor took place in Osaka, a city largely unaffected by the 1923 earthquake,“investing in shopping and leisure facilities at the central stations where commuters came together” As the first Hankyu department store opened at its Umeda station, this transit oriented strategy spread to a recovering Tokyo. In 1930, just after finishing the rebuilding of their flagship store, Matsuzakaya announced plans to directly connect their existing basement to the Ueno Hirokoji station on the Ginza subway line.

Today it seems impossible to conceive of a version of Japanese retail that doesn’t blend seamlessly into public transportation. Train stations, commuter and city subways alike, teem with the activity of countless vendors. “A walking tour guidebook for lovers published in 1932 suggested that as one of its five ‘date courses’, a young couple could visit ‘The Five Great Department Stores by Subway’, extolling that “the great thing about this tour was that, even if it was raining, the young couple could do all this without even having to put up an umbrella.”

It is possible here to note yet another evolutionary crossroads during the 1930’s - 1940’s, between depāto that had undergone the transformation from single vendor to hyakkaten and beyond and later railroad-affiliated depāto. As the former stores were being rebuilt post-earthquake in concert with new subway lines underground, many stores took after Matszakaya’s approach to ally themselves with the metropolitan subway. Railroad-affiliated depāto like Hankyu, Seibu in 1940, and later Tobu in 1962 continued their dogged pursuit of the sub-urban, sub-cosmopolitan commuter. Through their commitment to the larger interconnected environment, each of the five department store/hyakkaten-depāto strengthens their overall appeal to the average city dweller; a benefit that a suburban Seibu or Tobu store does not compound as more branches are built at distance from each other.

The basic operating diagram of a depāto across all franchises follows the same sectional construct: members of the public enter and leave from the basement or ground levels, travel upwards through private sale floors towards public functions of their choosing, ideally making purchases before their departure. Varying public programs - informal food halls, exhibition halls, even community colleges - found their place high on the sectional diagram. Use of western building methods yielded an additional benefit - flattened roofs capable of supporting sizeable program. True to form, the urban depāto placed public amenities on every viable rooftop without fail. In all but the most developed parts of Ginza, these rooftops enjoyed unmatched civic stature as the primary observation decks of their time - in the vein of Tange’s Metropolitan Government Building or today’s Oshiage Skytree.

Even as early as the 1920s, the urban depāto rooftops had begun to engage in a veritable arms race, one that continues to this day - spawning everything from theme parks to petting zoos, mini-golf courses to German beer halls. Each programming trend proffers keen insight into the urban conditions of the day. There is no doubt that much can be gleaned of the collective psyche from the popularity of amusement “skyparks” after WWII, or the recent demand for rooftop cocktail bars.

Whether or not a rooftop has been masterfully filled with program, the occupiable rooftop is a highly desirable component of the prototypical depāto - so much so that department stores without them will feign one with the use of artificial grass, as seen on Tobu in Ikebukuro. The flaws in these skilled facsimiles of free, public space are only noticed when an individual attempts to cross from one roof to the next. Even when all owned by the same conglomeration, pedestrian bridges are carefully drawn from retail floor to retail floor, eliminating the possibility of circumvention by a shrewd individual.

The primacy of rooftop space can be easily understood simply from the working diagram of the depāto. Its greatest value, apart from being a luxury not afforded to small commercial competitors, is as the satisfactory foil to the decidedly public subway basements of these shopping complexes. It completely obfuscates the meaning of a depāto name when one could be referring to either the transit node, the shop floors sandwiched in-between, or a public gathering space - effectively normalizing the private, cementing the enterprise into the experience of the city.

It is again worthwhile to note the marked difference in rooftop primacy in urban versus suburban environments. Although urban depāto rooftops had lost much of their coveted views to the post-war building boom, many suburban depāto are still the standard for building height where they stand. Yet railway depāto have not seen the same investment into creating outdoor sanctuaries atop their social programming. In general, Tobu and Seibu depāto rooftops only satisfy base utilitarian needs, catered to families with young children. Unlike the hyperaware urban depāto, suburban depāto rooftops presuppose an unchanging demographic: yet another point of flexibility the department store infrastructure supports.

Retrospectively, to chronicle the urban legacy of the Japanese depāto is to understand the exceptional circumstances that allowed it to exist. The existence of such a typology owes as much to Western architectural methods and department store precedent as it did Japan’s Hyakkaten mode of involved consumption and closed country policy.

The depāto cannot exist in a vacuum. Nor can it function as an anchor or draw based on its own merits, as observed in Seibu Los Angeles. It is merely ephemeral infrastructure space between two public arenas operating in perpetuity.

Many of the same observations on the depāto model without mass transit infrastructure in the 1960s can be applied to the depreciating suburban depāto of today. As shopping habits change, it has become more and more difficult for any physical retail store to attract footfall. Although the department store industry has seen declines in the lower two digits since the asset crisis hit, the rail line depāto has been the most affected by market insolvencies. Railway conglomerates have closed more than half of all suburban depāto in the last 15 years, which given the scale of their regional urbanity, is not particularly unexpected.

It is a testament to the efficacy of the urban depāto formula that with critical urban density and the endless capacity to adapt programmatically, new functions have been implemented that have brought sustaining growth. Ikebukuro’s Tobu and Seibu branches are great exemplars of surviving metabolism. Following current trajectories, the former will house only food services and restaurants while the latter continues expanding its current 400+ class dossier into Japan’s greatest community college.

As we near the 100th anniversary of the first transit depāto, we are also approaching a day where there is nothing left of the old department store. It’ll be anyone’s guess what comes next.

Introduction: Depāto as Urban Type

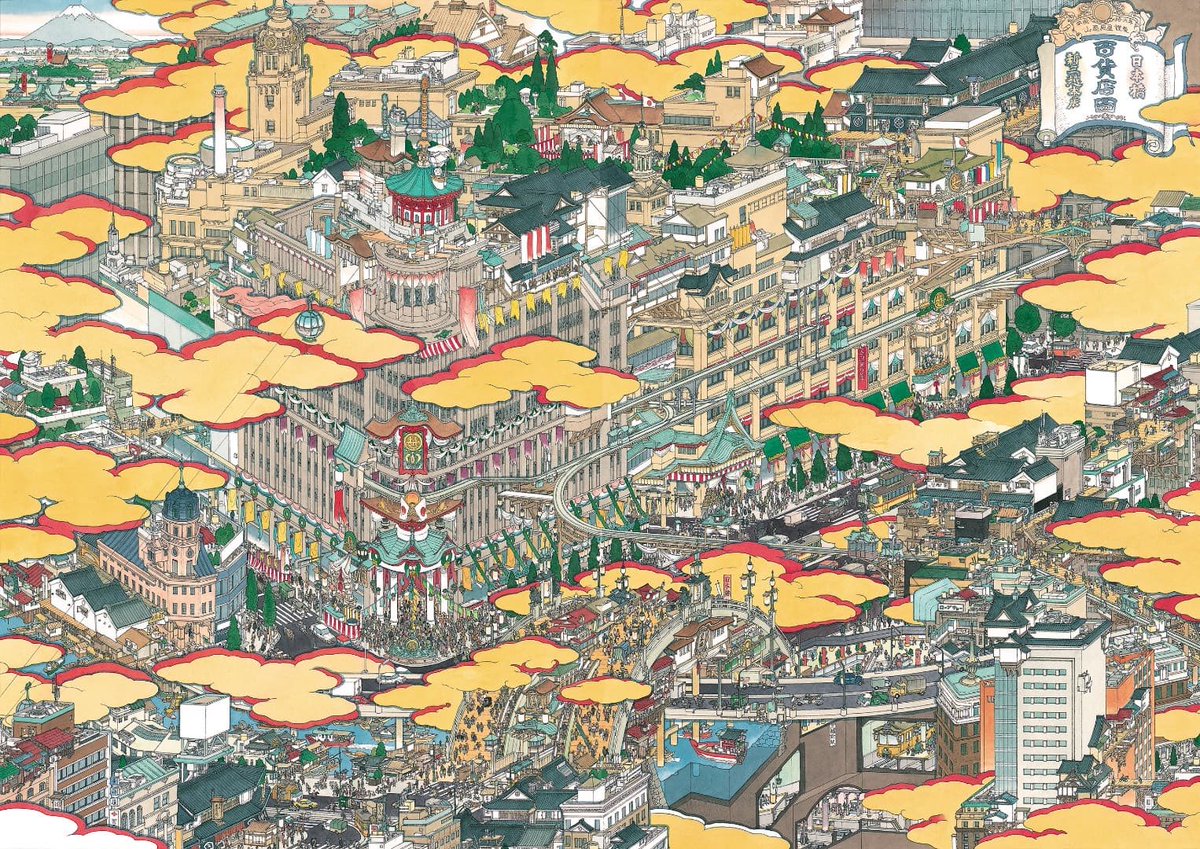

The genesis of the archetypal Japanese department store starts, predictably, in the buying and selling of small goods. Small shops unable to stave off the effects of almost periodic disaster - earthquakes, tsunamis, feudal war - are swallowed into larger conglomerates that sell their wares. The hyakkaten, meaning store that sells one hundred things, is owned by a single private entity. Not to be confused with the Western mall, which merely collects vendors in a serendipitous fashion, the Japanese depāto curates its offerings in a targeted fashion. It is a fact made abundantly clear through branding, signage, and staff uniforms.

Until recently, this was also expressed with the utmost clarity in its chosen architectural expression. The first Matsuzakaya in Ueno (1768) obeyed street lines and height limits, choosing to connect many storefronts under one roof. The next iteration of this same Matsuzakaya in Ueno, built in 1907, capitalized on the amount of land the predecessor territorialized - further adding one story and encasing the department store in a Western style facade. By 1917, only 10 years after the previous building was completed, a new flagship was completed at Ueno. Not only had it continued previous practices of swallowing land plots horizontally and sheath itself in a Chicago-esque exterior, this new development built upwards. The depāto towered over Ueno Park and surrounding neighborhoods, standing at least three stories taller than any other building within walking distance as recently as 1940.

The building was destroyed in the Kanto Earthquake of 1923 and had to undergo a 6 year long reconstruction. However, the choice to rebuild exactly as it was asserts that the size, programming, and chosen architectural form of the predecessor had elicited exactly the desired effect. No further architectural changes would be initiated at the building scale after decades of experimentation. The necessary building infrastructure for the depāto was now judged to be satisfactory and final - fit for manipulation at other scales and the testing of viable program.

Matsuzakaya - along with other pioneering stores Mitsukoshi, Shiragi, Takashimaya, and Isetan - all enjoyed this same period of formal stability and fiscal opportunity post-earthquake. It is during the late 1920’s, early 1930’s that the term depāto, shorthand for department store in English, became more commonly used over that of hyakkaten in reference to these businesses. It is fitting considering the role of the depāto in importing Western products. The impression is no doubt compounded by the unanimous decision of business owners to commission Western architects for their flagship stores.

Despite sharing a dictionary definition, there exist many organizational, spatial, experiential distinctions between the depāto and the preceding hyakkaten. One of the most fundamental differences being the way choreographed interactions manifested between goods and customers, exerting significant effect on their spatial orientation within a city.

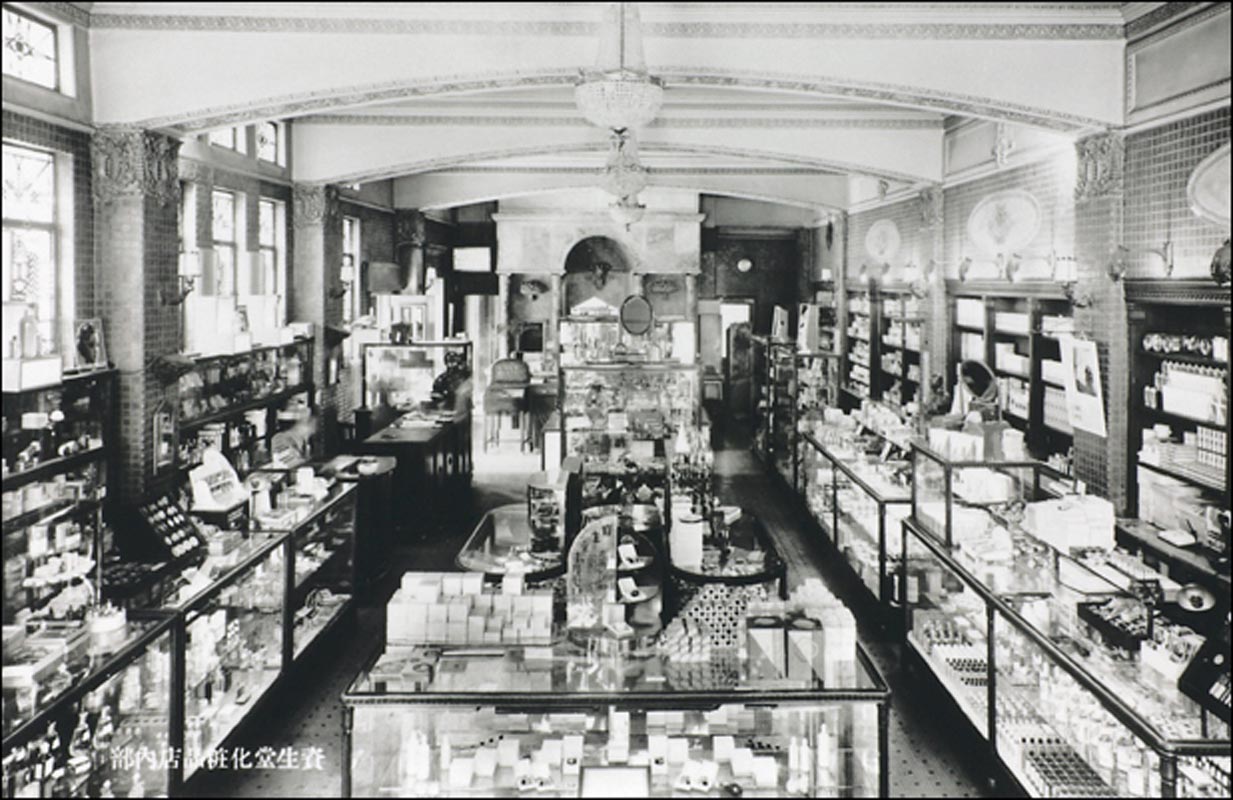

The primary function of a hyakkaten was a home base for travelling salespeople. “The big dry-goods stores...employed sales assistants to demonstrate goods to customers at their homes...much shopping could be done at home, as travelling salespeople came to call” The typical visitor to a hyakkaten did so for educational or experiential purposes - to learn about how to use the newest wares or discover them.

Megastores such as Shiseido purpose-built their stores to house these programs in that same hierarchy. Cramped sales floors were filled with every product imaginable behind glass and under counters, fulfilling only the barest utility for customers who wished to make specific purchases. Upstairs and in back gardens, generous classrooms and gallery halls extolling the virtues of their products sought to capture an audience. These included, but were not limited to, culinary classrooms, home economics workshops, training salons, and group dressing rooms.

If a visit to a hyakkaten could be classified as purposeful and time-consuming, the experience of a depāto was anything but. Matsukaya pioneered the spatial expression of accessible retail in Japan and “allowed customers to enter all floors with their shoes on” Before long, other department stores had followed suit, opting to“put in shop windows and glass display cabinets and installed wooden flooring, so that shoppers could walk in off the street without removing their shoes and freely view the merchandize” The direct connection between street and interior came in concert with other architectural tactics borrowed from Western counterparts.

New construction methods also contributed to this sense of the new public realm - making tall, lofty ceiling heights possible on sales floors, and bringing new scales of experience to previously domesticated retail. Widened halls and open shelving allowed for the sort of aimless browsing frowned upon in a typical hyakkaten. Dematerialized street level facades rendered interior activity visible to the exterior, as the depāto began to leverage convenience and transparency for exposure.

The deeply symbiotic relationship of department stores and train stations is one unique to Japan, made possible through the closed country policy that at once delayed both railroads and department store models from entering the country until they became contemporaneous with one another. European department stores and railways were allowed to develop at different timelines, with correlations that perpetuated density only where it already existed. Even without the embargo on foreign influences, the natural rhythm with which the country endured catastrophic natural disaster may have incited similar circumstances - a tabula rasa that encourages cross-pollination of extant ideas.

Earlier we mentioned the relative stability of the depāto as it stands within the ephemeral Japanese city of the mid 1900’s. This is not to say that the typology was immune to shifting landscapes, but that certain amounts of inevitable adjustment were well received within the depāto framework.

Even from their genesis, both models - urban depāto and suburban rail hybrid - had the foresight to allow flexibility within the building for public anchor spaces. An early example of the former built in 1929, Matsukaya, “boasted more than 78,000 square feet of display space, nineteen elevators, 6 escalators, air conditioning, restaurant seating for 1500 guests and a 1000-seat auditorium on the basement level, along with a roof-top children’s playground, small zoo, and an observatory and, as was customary of all department stores, a roof-top Inari [rice god] shrine” Comparing this vision of the urban depāto with its ancestor - Edo period kimono shops, standard bearers of luxury and hospitality - may prove sobering: The Mitsui family, owners of Echigoya in 1683, boasted of “a range of facilities including a customer toilet and garden”

The urban depāto keenly identified infrastructural needs of all types that weren’t being met in entire neighborhoods, regardless of function or expertise. So as long as the urban amenity could be replicated below, within, or above the depāto, it was tested in practice. For these reasons, urban depātos underwent frequent interior renovations, as often as once every 7 or 8 years to match the speed of urban trends.

In contrast to the cornucopic offerings of Matsukaya and its peers, Hankyu Railway’s groundbreaking Umeda terminal store (also completed in 1929) , standing “8 floors above ground and 2 basements above the ground” could only report to its seamless integration with commuter lines and modest food service. It is a testament to Hankyu’s knowledge of their commuter base that those two factors alone were enough to create a resounding success. As affordable, casual meals of “Rice Curry / Sorrise [cheap rice dish flavored with worcestershire sauce] etc. were offered to the commoners, and lunch box sales were made to people leaving for trips”, the terminal department store became ingrained in the daily lives of each Hankyu commuter.

This asymmetry of programmed space corroborates the compatibility of depāto framework for a variety of scales and contexts. For urban institutions like Matsukaya, the manner with which programs were being installed and deployed as attractions to the public wasn’t simply based on competition between two rival companies between niche groups. Their appeal had to be as broad as the ridership that rode past their basement entrances each day; as all inclusive as the “hundred goods” they carried in stock. As one depāto curator put it: “There are no public museums in Shinjuku and Ikebukuro, but Seibu has a museum at Ikebukuro and Isetan one at Shinjuku. There are still few public museums in Japan compared to Europe of the United States, so it is up to depāto to fill this role”

Hankyu terminal station could not compete with the upper-class urban depāto in attractions, but it didn’t necessarily have to. The draw of the railway depāto was never meant to fully entrap the commuter or fulfill his/her needs in entirety. The department store was merely one of many attractions programmed by railroad conglomerates to promote activity along their entire geographic profile. Hankyu Railways had developed, at one point, “a zoo, a hotspring resort, the Takarazuka revue theatre, a baseball stadium (and team) on land along its line” as mechanisms for boosting ridership. By considering this larger network of amenities, the two model approaches start aligning: one presumes the activity of customers along a train line in perpetuity; the other must hope against all hope that the vertical ascension of customers from subway to roof never ceases.

Lessons from Los Angeles: Seibu on the Miracle Mile

As a transit-oriented, context sensitive urban institution, the depāto has seldom translated beyond the limits of Japan. However, it is in the interest of understanding the typology’s failure outside of regional environmental influences that Seibu Wilshire of Los Angeles becomes a worthwhile point of investigation.

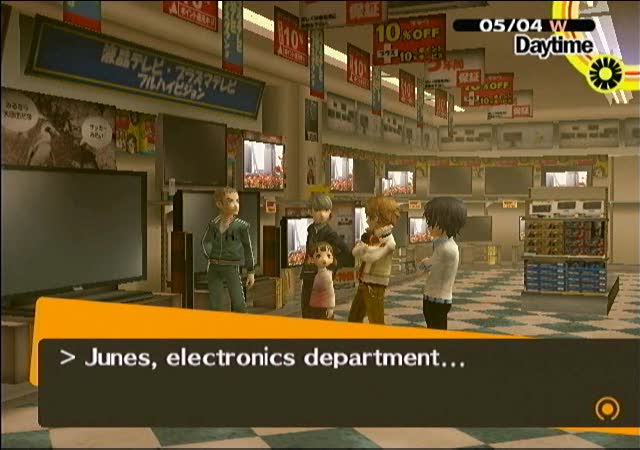

The department store was a short lived venture put forth by aforementioned Seibu Railways in 1962, then at the height of its success back in Japan. Of the hyakkaten, it is observed that “Clearly, depāto mount exhibitions of foreign art to attract customers...the merchant ethic of the Tokugawa era condoned the pursuit of profit only when coupled with a sense of duty and social responsibility” To many locals, Seibu Wilshire’s primary draw as an establishment was anticipated to be exactly that - an exhibition of foreign art to attract customers. “Housed in a block-long, four-story building with just touches of Japanese decor—a cluster of lanterns, an occasional screen and a few Nisei girls in geisha costume” the building’s constrained exterior fell far short of this expectation. The endeavor wasn’t just one of misaligned values or supply chains, it was a mismatch of the urban functions American department stores and depāto respectively fulfilled in their contexts.

One such key mismatch would be the Seibu Wilshire’s location on the Miracle Mile. Although the siting conformed to American department store logic - that a collection of brand names would attract attention and activity - Seibu could not feasibly rely on that logic to sustain an urban presence.

For another ,the architectural execution of the idea contributed to a failure from which there could be no recovery. Seibu’s department store interiors had regressed from the open merchandising shelves into old glass cabinet conventions of the hyakkaten, offering little room for the ad-hoc interactions that defined the depato as an civic experience. The roofscape was given entirely to one privatized dining service with no possibility of architectural flexibility to juxtapose and test programmatic intentions to find the right rooftop draw. Finally, what little space existed at the ground floor to welcome the rare pedestrian was given to isolating and occupiable stone gardens instead of furthering notions of an expanding street. What Seibu Los Angeles did possess was an iconic facade and memorable architectural form, which may have been yet another impediment to being renovated easily and often and perhaps saved from ruin.

The rail-oriented depāto that Seibu characterizes is one that forsakes specific draws for general appeal. While this is a successful approach to diverting flow from a pre-existing commute, generality is less appealing as a destination for the customer behind the wheel. “Seibu of Los Angeles is essentially an American store with all the usual U.S. retailing gimmicks, including a two-deck parking garage and a roof-garden restaurant with bar” observed a reporter visiting Seibu for the first time, “Its merchandise is predominantly Western-styled, and only 60% of it is made in Japan” For Seibu Chairman Yasujiro Tsutsumi the real battle was to proceed “from novelty to sustained success”, yet the American department store must rely on novelty for relevance, as the freedom of the automobile is capable of recalibrating everything spatially to be of near equal convenience.

Within this transit desert, Seibu could not have benefited from its proximity to neighboring anchor stores the same way it did in the city. In Ikebukuro, architecture, transit, retail, and streetscape were all under the control of one entity. Thresholds could be manipulated, even dissolved in instances, shortcuts removed. However, no established line of travel existed to force interaction between the department store and direction of traffic in an automotive urbanism.

Works Cited

Old Tokyo, www.oldtokyo.com/matsuzakaya-department-store-ueno-1907-1940/.

“Department Store Closures Mark End of an Era.” The Japan Times, www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2016/09/28/business/kashiwa-sogo-closure-marks-end-era-emporiums/.

Francks, Penelope. The Japanese Consumer: an Alternative Economic History of Modern Japan. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Fujioka, Rika. “Japanese Department Stores.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Business and Management, 2018, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190224851.013.95.

“Hankyu Corporation.” History of Franklin Covey Company – FundingUniverse, www.fundinguniverse.com/company-histories/hankyu-corporation-history/.

Isozaki, Arata. The Island Nation Aesthetic. Academy Editions, 1996.

Kira, Moriko, and Mariko Terada. Japan towards Totalscape: Contemporary Japanese Architecture, Urban Planning and Landscape: NAI Publishers, 2000.

Kuan, Seng, and Yukio Lippit. Kenzo Tange: Architecture for the World. Lars Müller, 2012.

Macpherson, Kerrie L. Asian Department Stores. Taylor & Francis, 2016.

Matsunosuke, Nishiyama, and Gerald Groemer. Edo Culture: Daily Life and Diversions in Urban Japan: 1600-1868. University of Hawaii Press, 1997.

Oshima, Ken Tadashi. Arata Isozaki. Phaidon Press, 2009.

“Retailing: A Touch of Tokyo.” Time, Time Inc., 23 Mar. 1962, content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,829151,00.html.

“Seibu Department Store Interior, 1962.” Miracle Mile Residential Association, 10 June 2015, miraclemilela.com/the-miracle-mile/historical-photos/seibu-department-store-interior-1962/.

Stores, Ltd.." "Seibu Department. “Seibu Department Stores, Ltd.” The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th Ed, Encyclopedia.com, 2018, www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences-and-law/economics-business-and-labor/businesses-and-occupations/seibu-department-stores-ltd.

Tobin, Joseph J. Re-Made in Japan: Everyday Life and Consumer Taste in a Changing Society. Yale U.P.

“開業50周年「西武船橋」は、なぜ閉店するのか | 百貨店・量販店・総合スーパー.” Tokyo Business Today, 27 Feb. 2018, toyokeizai.net/articles/-/210558?page=2.

Old Tokyo, www.oldtokyo.com/matsuzakaya-department-store-ueno-1907-1940/.

“Department Store Closures Mark End of an Era.” The Japan Times, www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2016/09/28/business/kashiwa-sogo-closure-marks-end-era-emporiums/.

Francks, Penelope. The Japanese Consumer: an Alternative Economic History of Modern Japan. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Fujioka, Rika. “Japanese Department Stores.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Business and Management, 2018, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190224851.013.95.

“Hankyu Corporation.” History of Franklin Covey Company – FundingUniverse, www.fundinguniverse.com/company-histories/hankyu-corporation-history/.

Isozaki, Arata. The Island Nation Aesthetic. Academy Editions, 1996.

Kira, Moriko, and Mariko Terada. Japan towards Totalscape: Contemporary Japanese Architecture, Urban Planning and Landscape: NAI Publishers, 2000.

Kuan, Seng, and Yukio Lippit. Kenzo Tange: Architecture for the World. Lars Müller, 2012.

Macpherson, Kerrie L. Asian Department Stores. Taylor & Francis, 2016.

Matsunosuke, Nishiyama, and Gerald Groemer. Edo Culture: Daily Life and Diversions in Urban Japan: 1600-1868. University of Hawaii Press, 1997.

Oshima, Ken Tadashi. Arata Isozaki. Phaidon Press, 2009.

“Retailing: A Touch of Tokyo.” Time, Time Inc., 23 Mar. 1962, content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,829151,00.html.

“Seibu Department Store Interior, 1962.” Miracle Mile Residential Association, 10 June 2015, miraclemilela.com/the-miracle-mile/historical-photos/seibu-department-store-interior-1962/.

Stores, Ltd.." "Seibu Department. “Seibu Department Stores, Ltd.” The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th Ed, Encyclopedia.com, 2018, www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences-and-law/economics-business-and-labor/businesses-and-occupations/seibu-department-stores-ltd.

Tobin, Joseph J. Re-Made in Japan: Everyday Life and Consumer Taste in a Changing Society. Yale U.P.

“開業50周年「西武船橋」は、なぜ閉店するのか | 百貨店・量販店・総合スーパー.” Tokyo Business Today, 27 Feb. 2018, toyokeizai.net/articles/-/210558?page=2.