Haga Hygge - as part of The Urban Atlas: Gothenburg

with Erin Kim, Samantha Monge Kaser, and Jincy Kunnarythril; with critics Alan Plattus and Andrei Harwell and additional support from the City of Gothenburg - Sweden, Chalmers, Älvstranden, and White Arkitekter

with Erin Kim, Samantha Monge Kaser, and Jincy Kunnarythril; with critics Alan Plattus and Andrei Harwell and additional support from the City of Gothenburg - Sweden, Chalmers, Älvstranden, and White Arkitekter

“HAGA: Cosy, Shopping & Fika”

- official Haga district signage slogan, found on banners throughout

As part of the YSoA’s first urban workshop in the area, we worked with local contributors to create “The Urban Atlas”, a wayfinding document of the city’s current and past urban conditions.

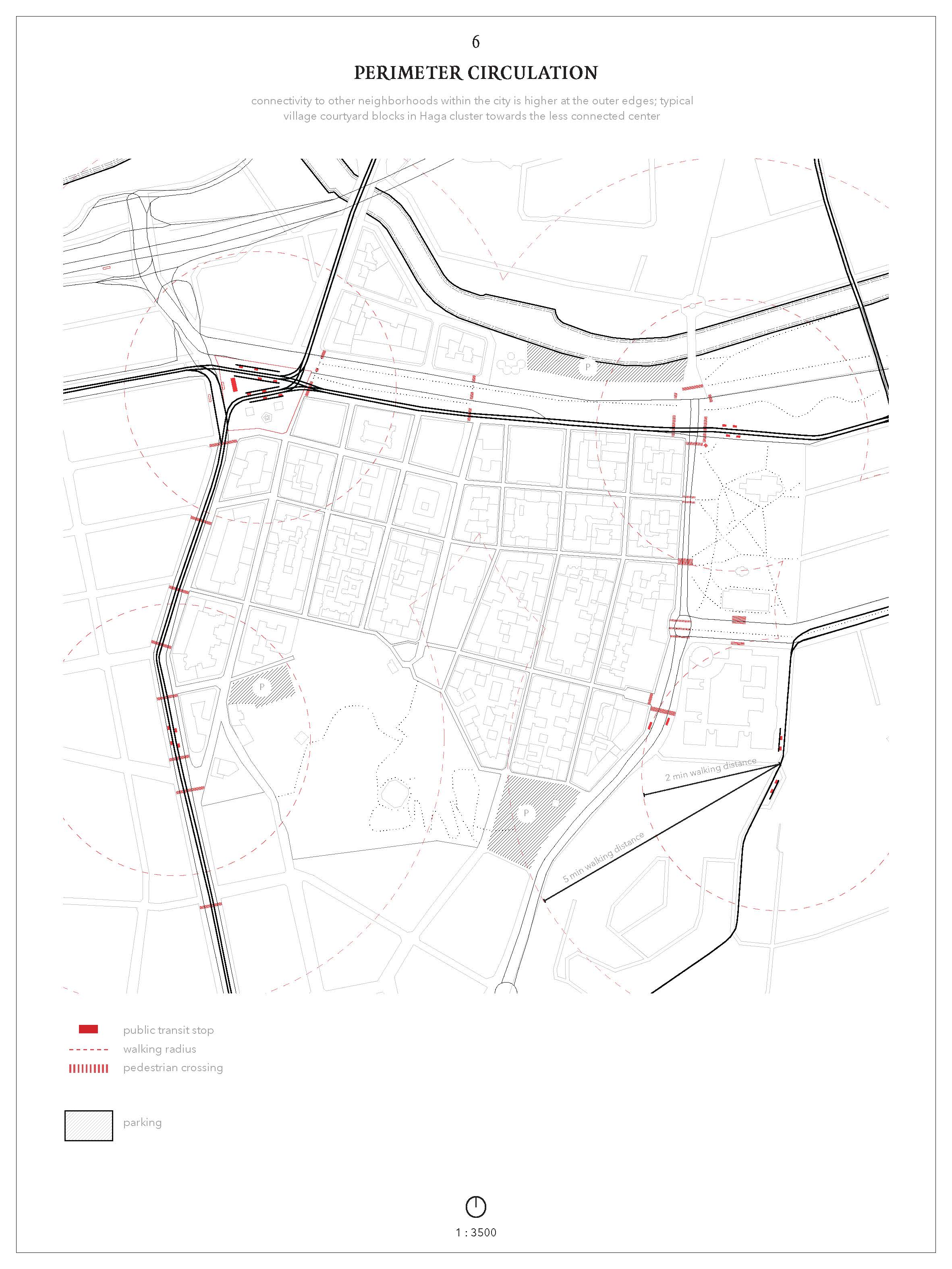

The first planned suburb outside of city fortifications, Haga was first defined by its natural surroundings and the threat of invasion. In groups of four, we studied and researched districts in Gothenburg to aid the city in positioning a stance for or against developments in the area.

The neighborhood of Haga is at once a tourist destination as well as a highly-desired

residential area. It endured periods of demolition and reconstruction, most recently mass

demolition and rehabilitation efforts in the late 1970s. The versatile urban fabric of this

small parish absorbs private interests around its perimeters, vibrant commercial activity

across its center, and community-oriented housing within its block interiors.

In the following large-scale urban studies, we studied maps from the 16th century to present day to determine the formal strategies that created this much-loved district.

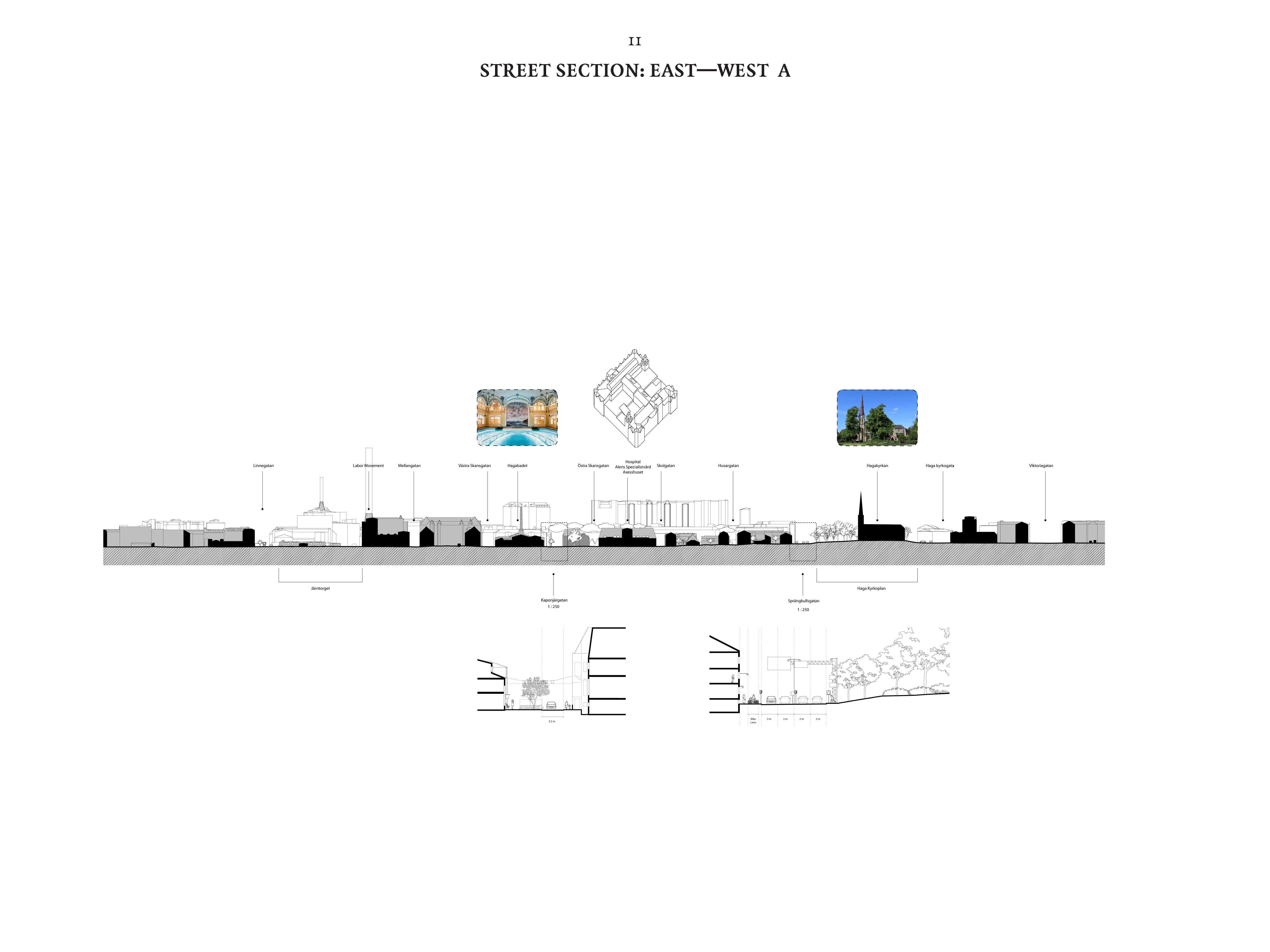

We discovered a forgotten canal approach that formed the road to Skansen Kronen, a mountain watch tower, and unparcelled further the inflections that the castle moat, canals, and other waterways may have contributed to in present-day Haga.

We discovered a forgotten canal approach that formed the road to Skansen Kronen, a mountain watch tower, and unparcelled further the inflections that the castle moat, canals, and other waterways may have contributed to in present-day Haga.

Part of the appeal of living in Haga, apart from its proximity to city center and higher learning institutions, lay in the rich interior life of inner block courtyards unique to the area. Locals would often refer to them automatically as possessing a certain “

je ne sais quoi” central to the overall spirit of the storied district.

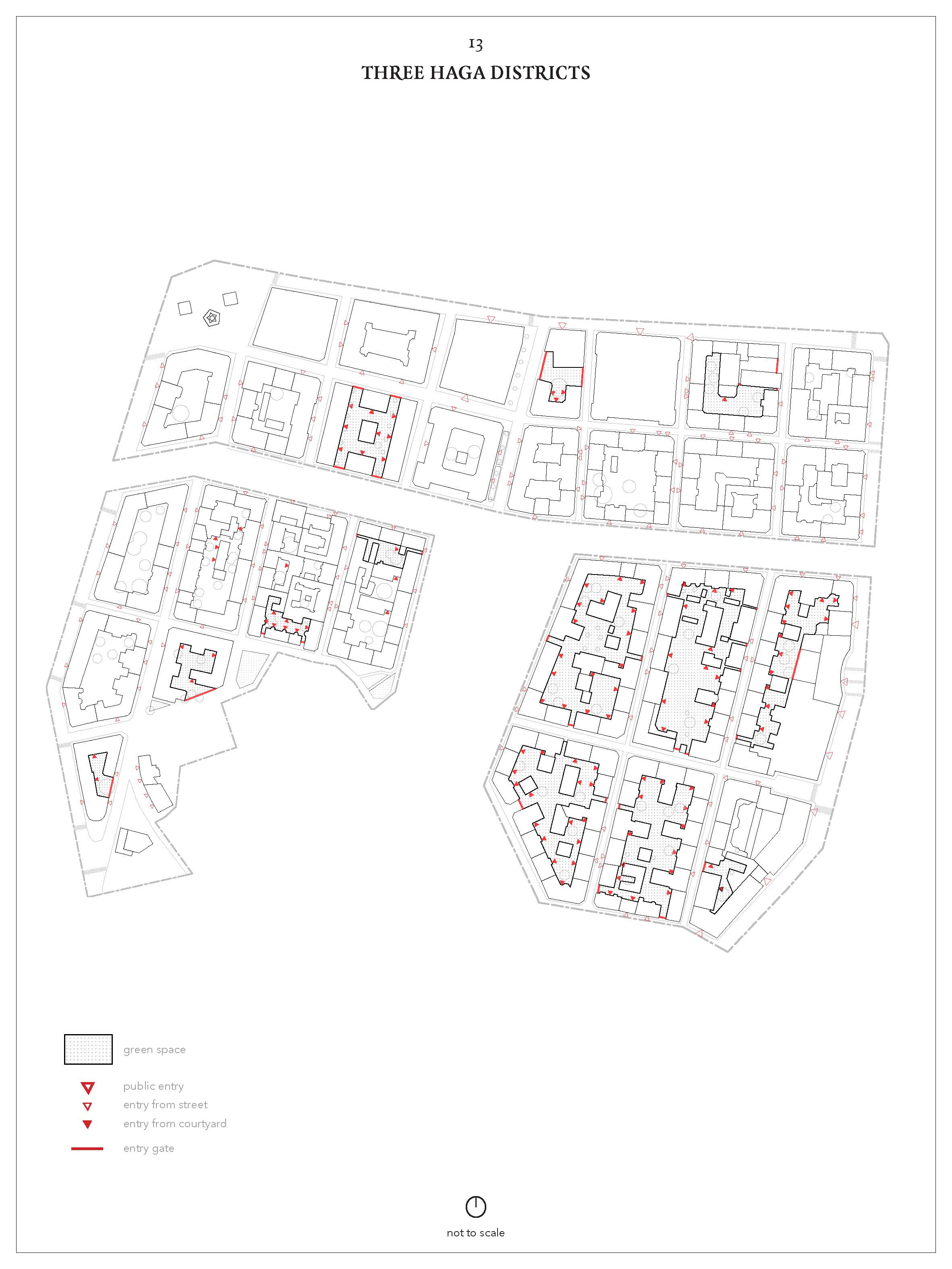

Almost by chance, we started counting the amount of unique doorways to these residential courtyard buildings - which led to the realization that Haga’s most characteristic courtyard communities shared one strong correlation: the ratio of interior doorways to street openings.

Almost by chance, we started counting the amount of unique doorways to these residential courtyard buildings - which led to the realization that Haga’s most characteristic courtyard communities shared one strong correlation: the ratio of interior doorways to street openings.

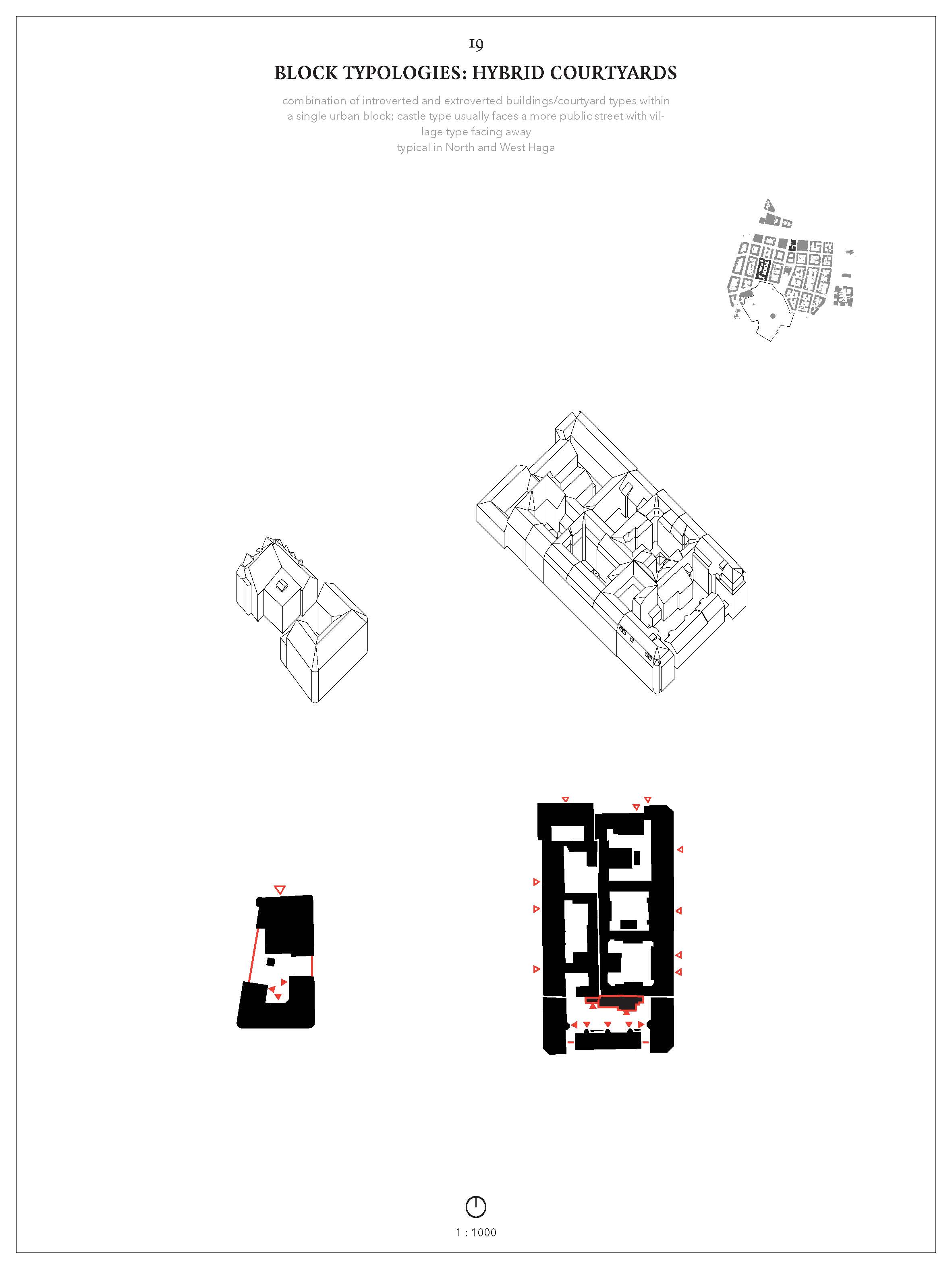

When occupants could only enter their buildings through the interior courtyard, it resulted in a fully communal courtyard experience. Once occupants could enter from outside, even if only a few instances existed in a block, the part of the courtyard that neighbored their building would become a more private backyard that could be fenced off to access.

Using this method, we successfully identified the three distinct neighborhoods of Haga that locals typically associate as having separate, if hard to describe, personalities - with East Haga having the most communal, sought after courtyard communities.

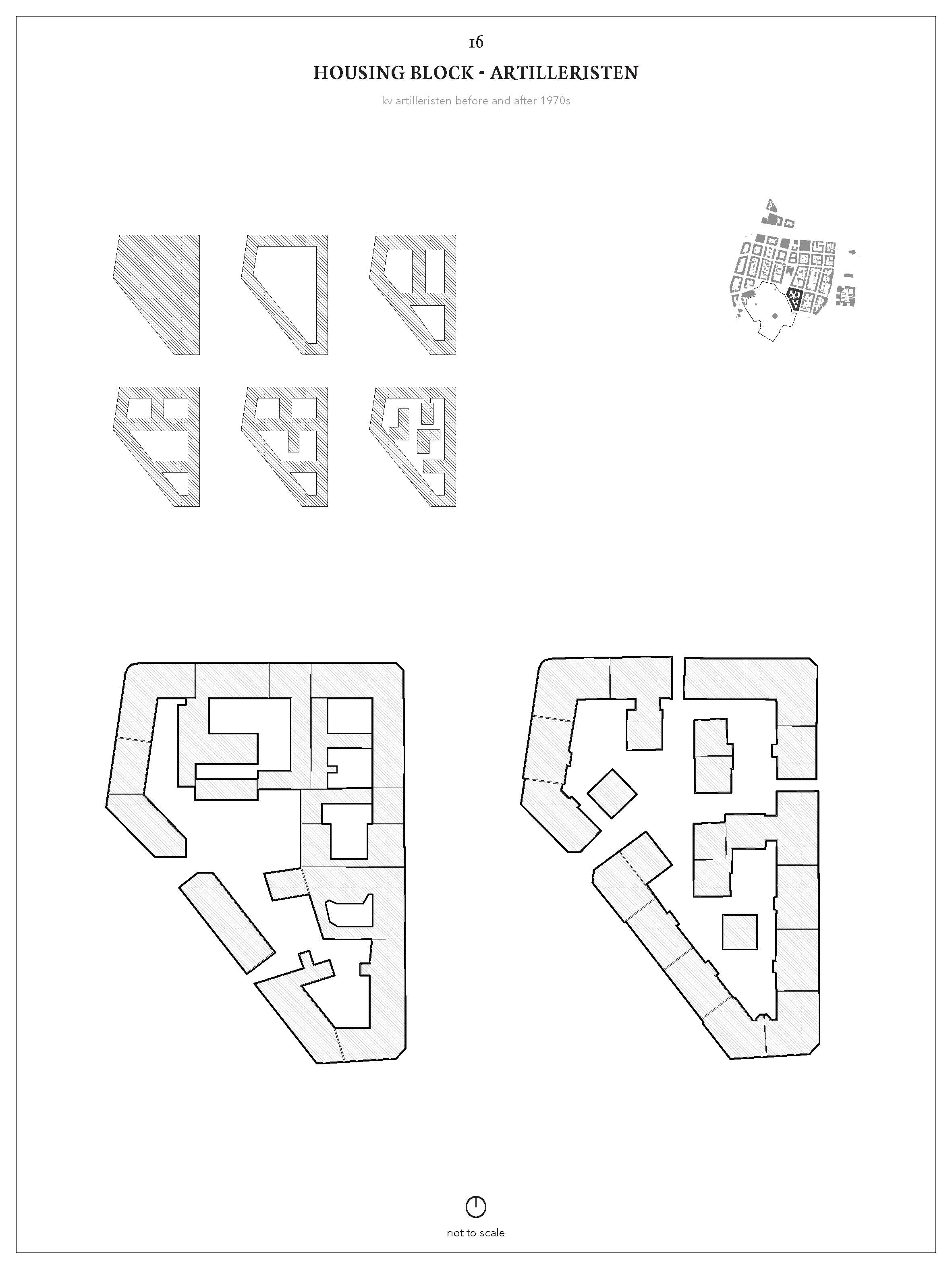

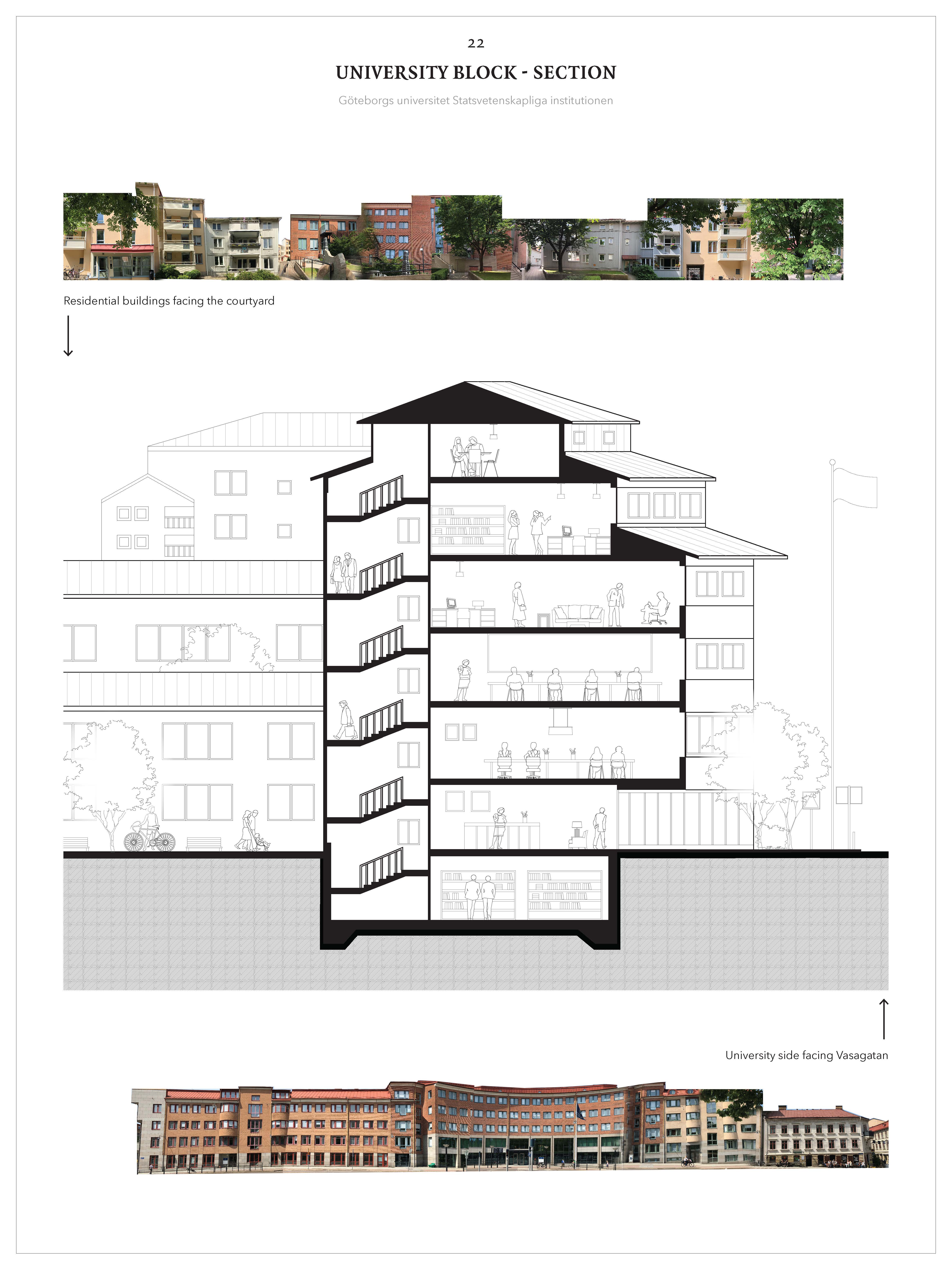

Part of our research also proposed a second look at the possibility of integrating larger-scale entities into the low-rise, high density fabric of Haga without disrupting existing patterns of habitation.

We used the University of Gothenburg as a precedent for analysis - noting that it was halfway prototypically “Haga”, and halfway a megablock.

We used the University of Gothenburg as a precedent for analysis - noting that it was halfway prototypically “Haga”, and halfway a megablock.

Our conclusion and recommendation to members of the Gothenburg community was that while there was possibility for successful integration, it would have to come in the form of multiple buildings and forsake the mainstream idea of maximizing street frontage. By focusing activity on the block interior, the proprietary activity density that Haga blocks enjoy would continue to propegate.